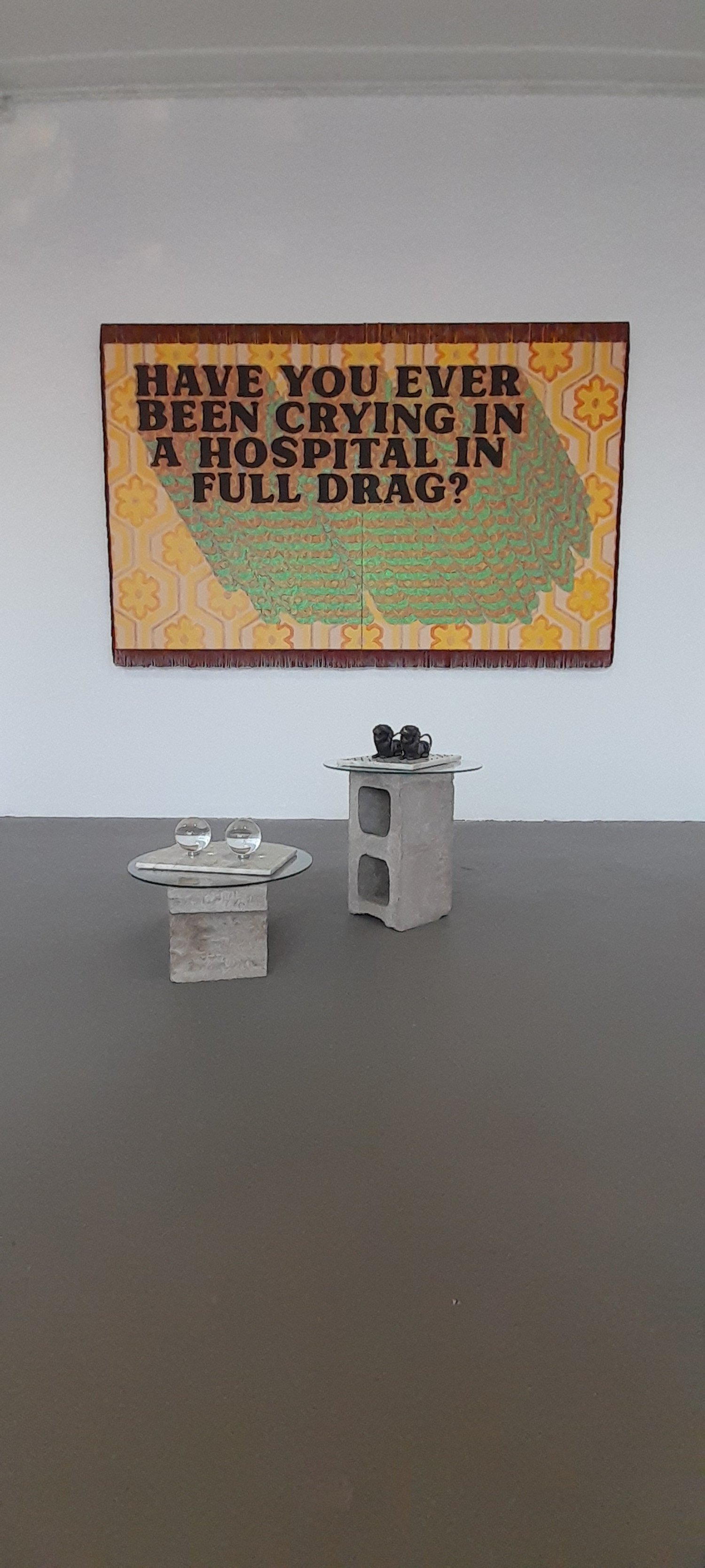

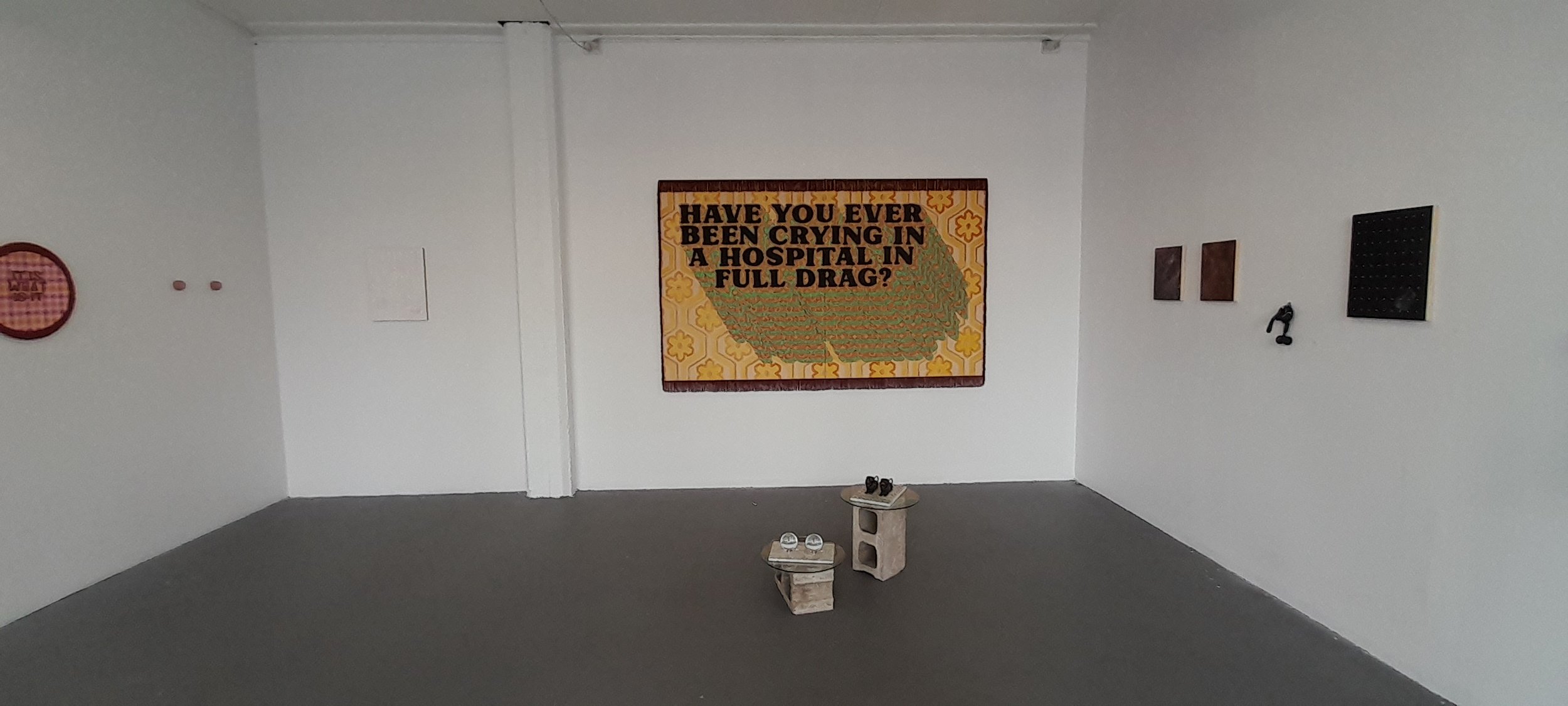

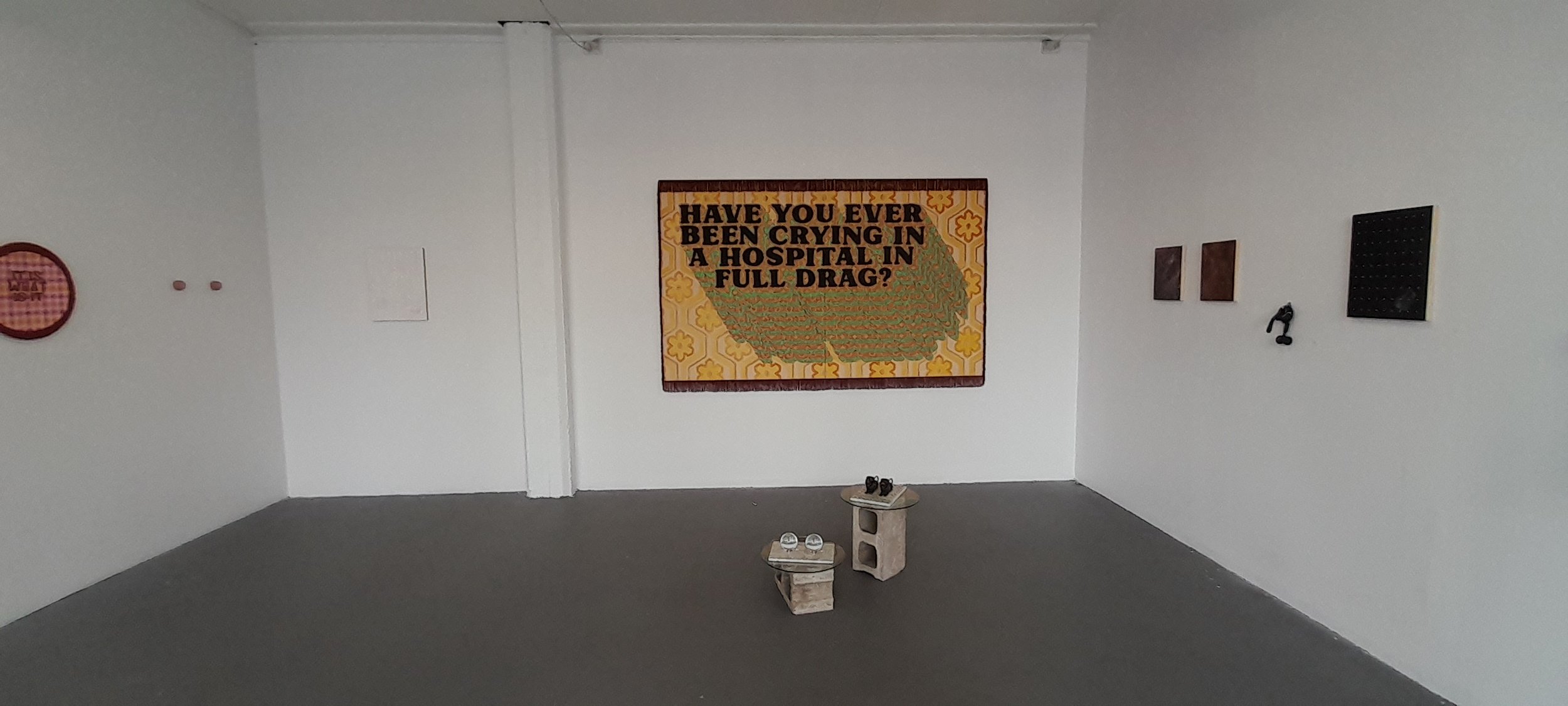

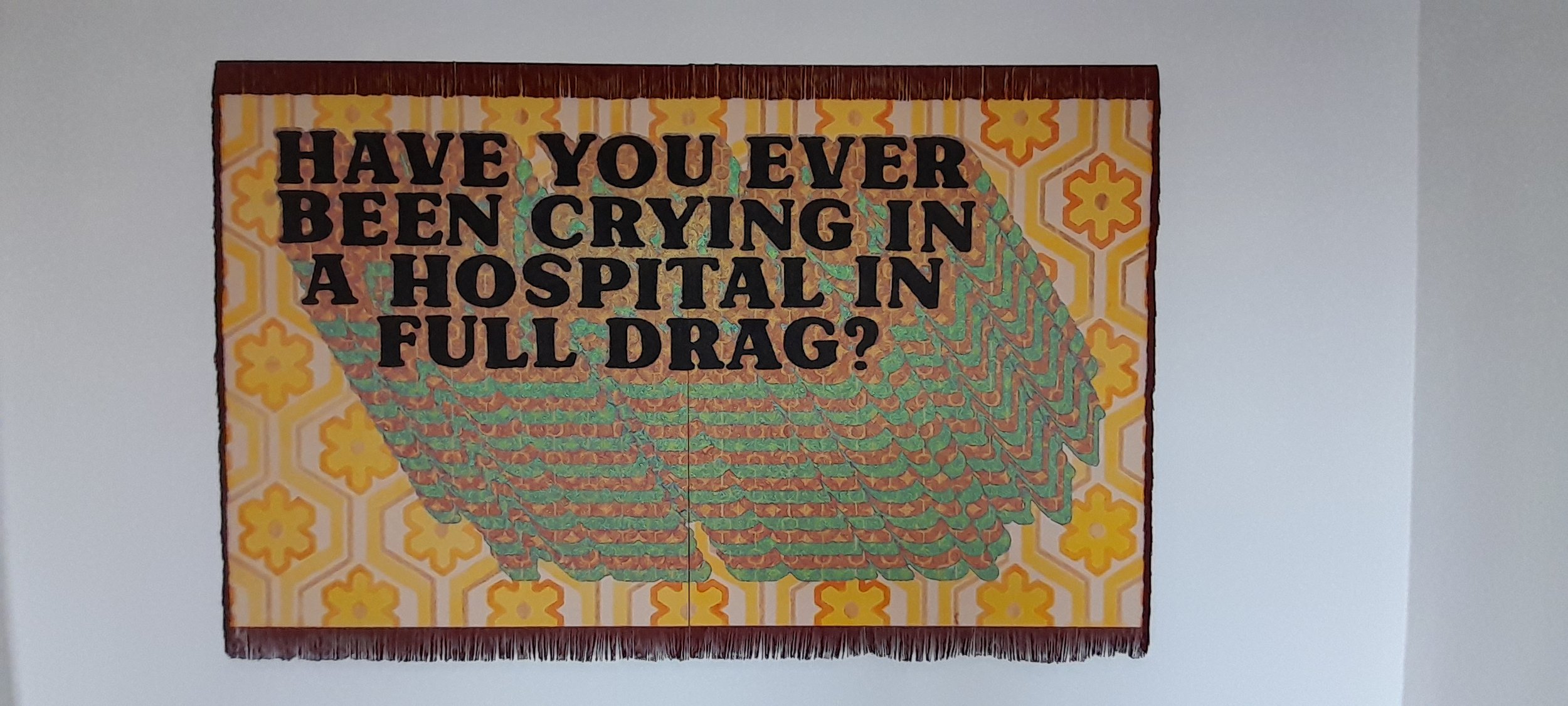

Have you ever been crying in a hospital in full drag?

Have you ever been crying in a hospital in full drag?

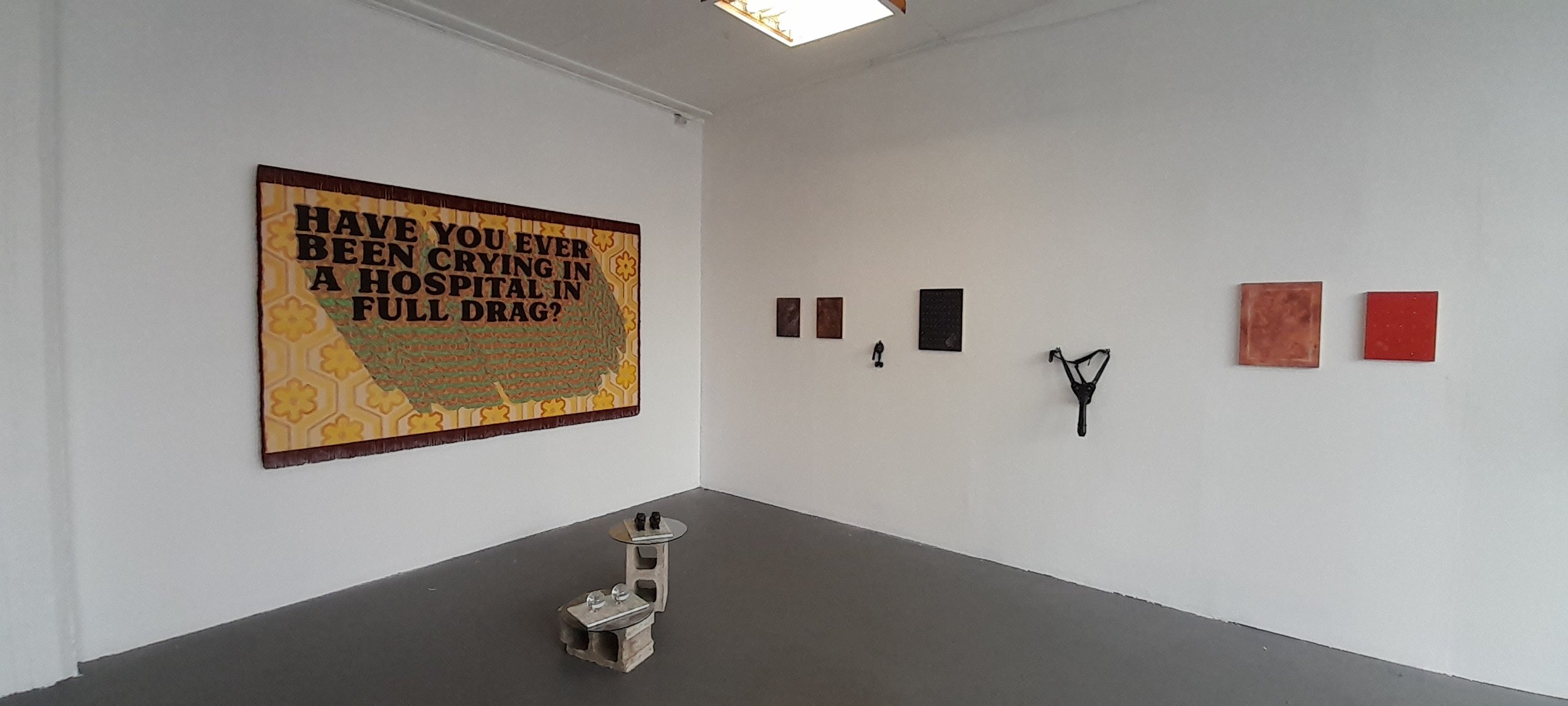

curated by Ellie Lee-Duncan

Never Project Space

2022

Catalogue text:

Queer is a category, but it’s also a refusal of categorisation. Queer can be whatever exists as non-normative. What is fantastic, different, strange, and subversive. Queer, argues Amelia Jones, resists static definition. Instead, she says, it is ‘that which indicates the impossibility of a subject or meaning staying still, in one determinable place.’

Brittany Walker Smith, Caitlin Devoy, and Shannon Novak create artworks that are complex and defy straightforward interpretations. Each creates highly staged attempts to contest gender and sexuality, suggesting that they are not, after all, innate or static concepts, and are instead riddled with contradictions.

How can aesthetics portray experiences of gender and sexuality as playful, positive, and ameliorative?

Camp is a queer aesthetic method which these artists each embrace. The term likely finds its etymology in the French term se camper, ‘to assume a proud, bold, or provocative posture, to strike a pose.’ Camp was famously defined by writer and critic Susan Sontag in her 1964 essay ‘Notes on camp,’ which she dedicated to Oscar Wilde, an icon of the camp sensibility. In her essay, Sontag defines camp as ‘the spirit of extravagance’ and traces it from the French King Louis XIV, through to modern mainstream popular culture, and particularly embraced by predominantly queer communities in America.

However, Sontag’s argument on camp stripped away homosexuality to the point where Moe Meyer writes that Sontag ‘sanitized’ camp of its queer connotations. Instead, Meyer argues that camp was, and continues to be, ‘the production of gay social visibility’. As well as a certain attitude, camp revolves around performance and specific materials, with the tone of postmodern irony.

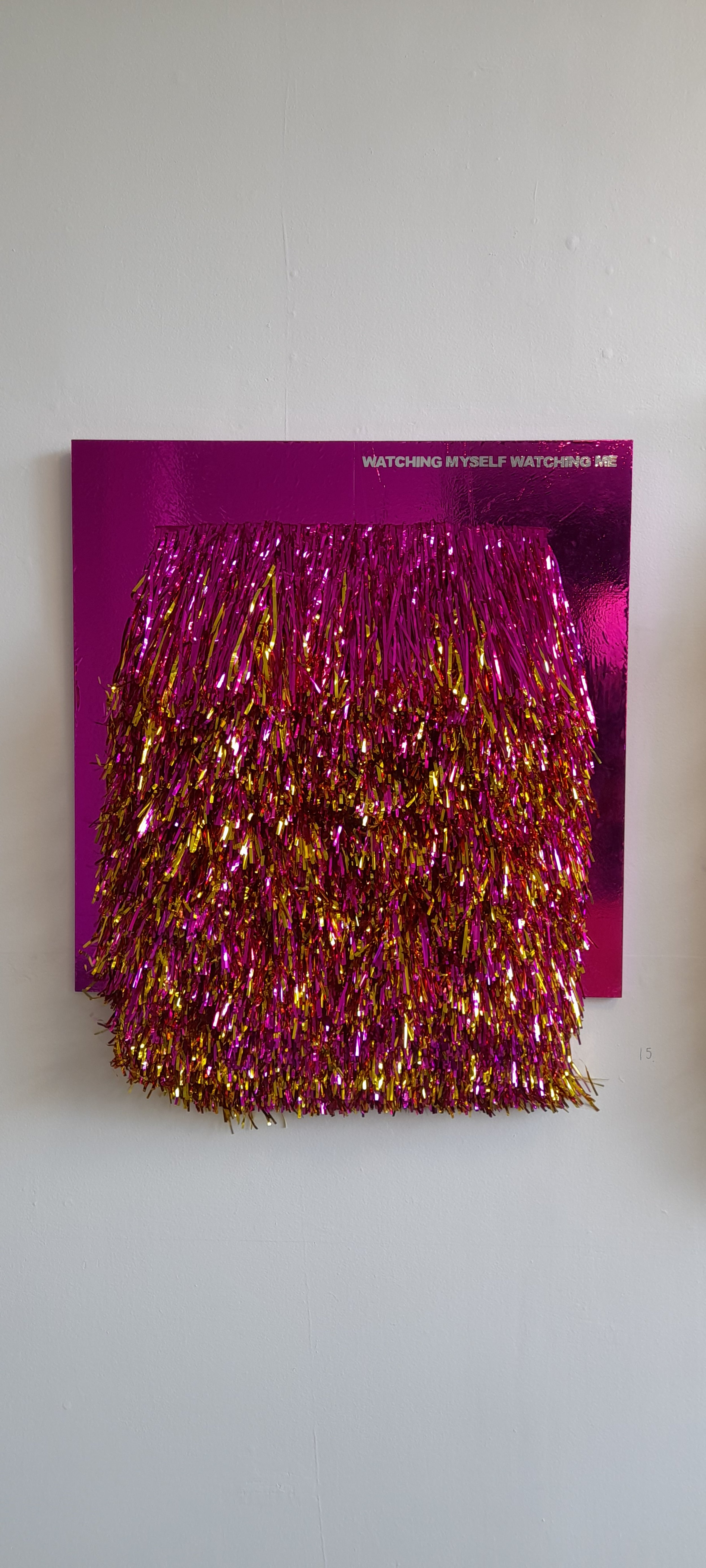

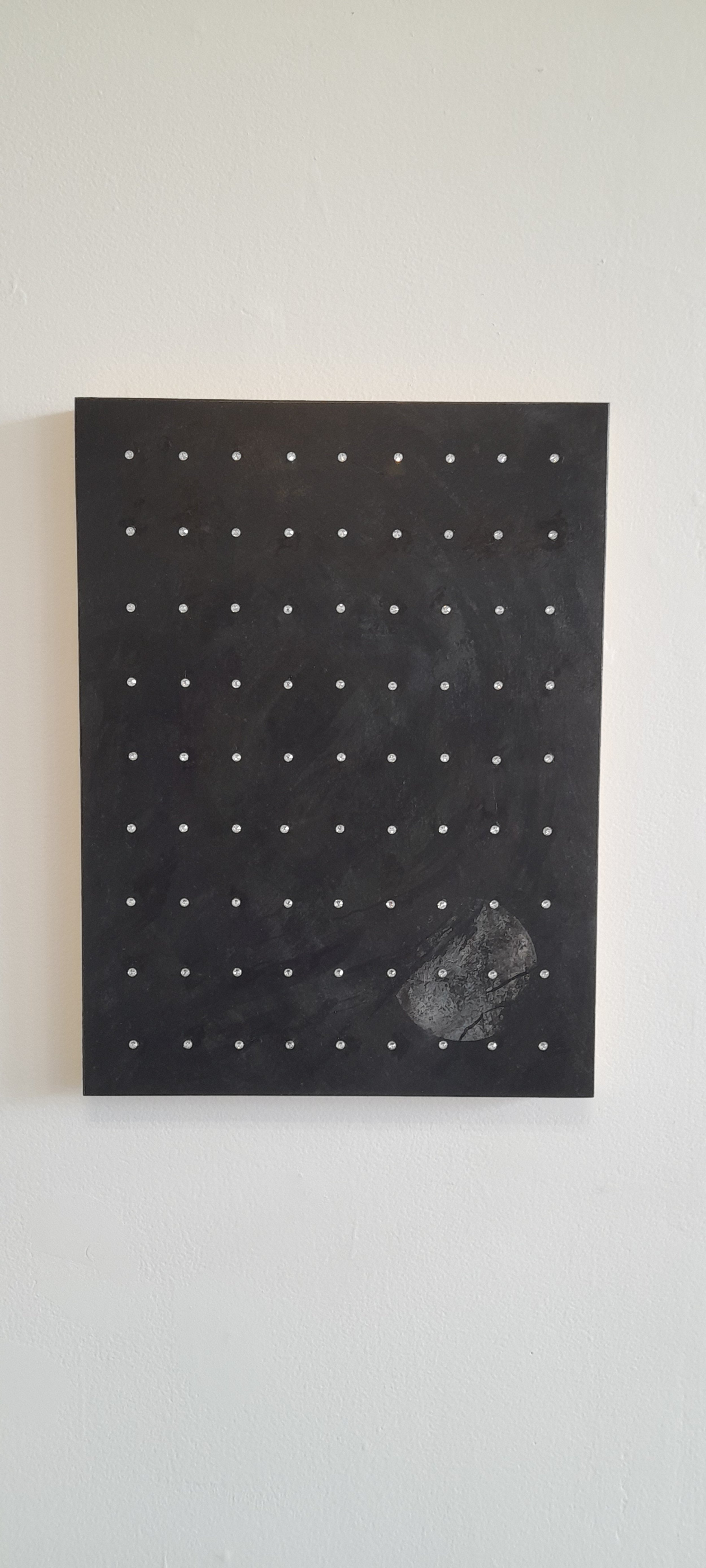

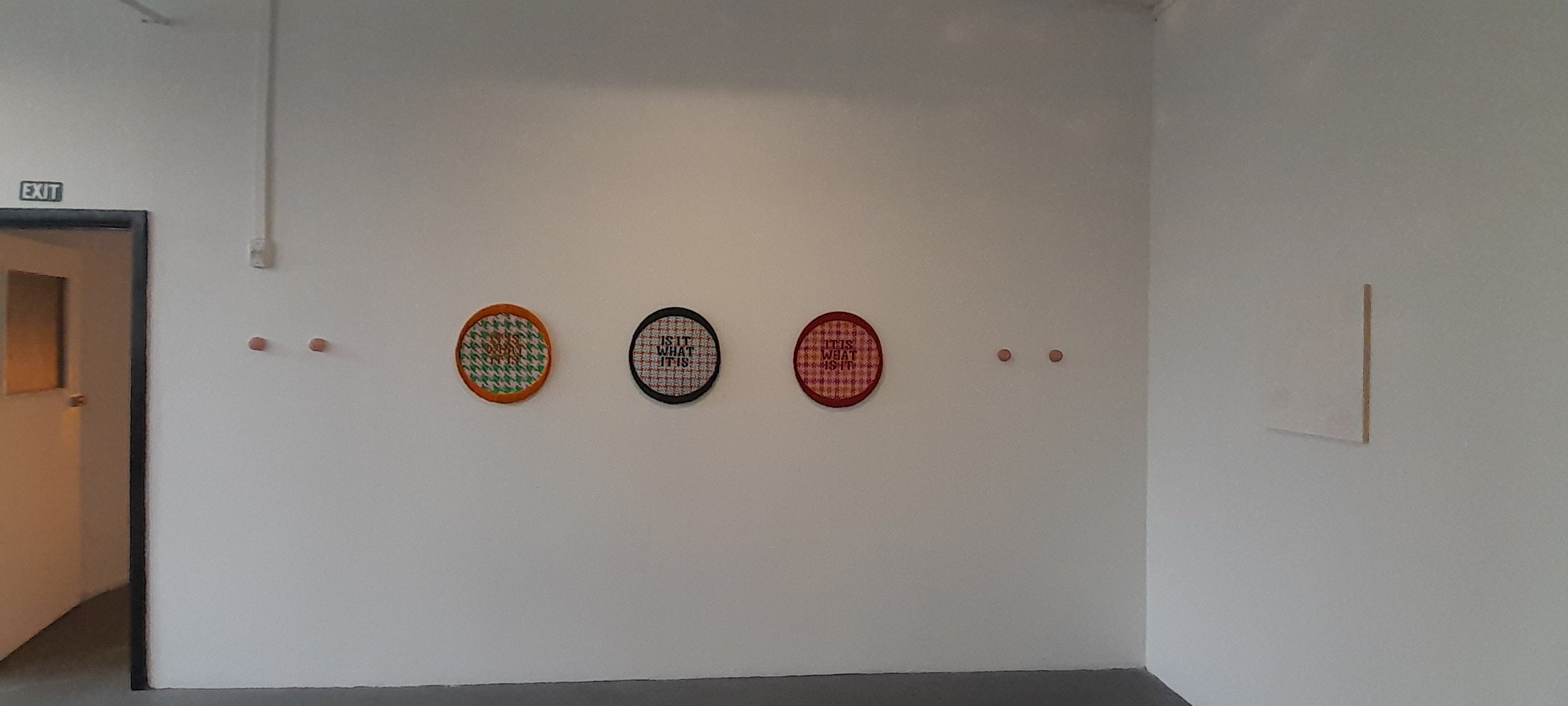

The works by these artists all explore queer modes of representation, where creativity against normative constructs is expressed through silicone, swarovski crystals, tinsel, glitter, and paint. Elements include pieces from ‘low-brow’ or cheaply available materials and, through their rich surfaces, draw viewers into a deeper engagement with social meanings around camp and bodies.

Brittany Walker Smith, Caitlin Devoy, and Shannon Novak each create a healing approach to camp, where each artist ‘extract[s] sustenance’ from the dominant culture and instead repurpose it for its positive and playful potential.

American art critic Clement Greenberg described kitsch as a ‘reservoir of accumulated experience’ in direct opposition to the canon of academic or high art. However, recent queer scholars such as Scott Herring, Elizabeth Freeman, and Jack Halberstam have challenged this, by instead considering kitsch as a strategic queer aesthetic which appropriates pop culture and prizes the ability to ‘relay [...] sentiment and affect’.

Philosopher Eva Sedgwick argues that the affirmative potential of camp aesthetics to queer communities can be realised when an artist lingers on the sensations of nostalgia and sentimentality.

Likewise, Walker Smith’s work is created out of a ‘material obsession with kitsch,’ and nostalgic reflection that as children we are ‘allowed to enjoy’ the healing process of play.

Within queer counterpublics, camp is a process to denaturalize and appropriate gender through performance and costume. Life becomes an opportunity to make a spectacle, to make a spectacle of oneself and Sontag says, ‘to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role’. Linda Hutcheon argues that camp is similar to postmodernism in its use of irony and reflexivity. Central to camp is the intent to do something extraordinary, regardless of functionality. The essential component here is decoration, excess, reiteration, and the attitude more is more. Devoy’s use of camp allows her works to use a ‘slippery subversive nature of humour to reveal vulnerabilities, criticize sexism, and challenge binary representations of masculinity and femininity’.

Within the LGBTQI+ communities, people are affected by trauma, anxiety, depression, and suicide at catastrophically high rates, both globally and in Aotearoa. Novak’s work is deeply informed by this- he’s previously partnered with OUTline, a free resource for those who identify as LGBTQI+, as well as being vocally opposed to conversion therapy, actively working towards its ban in Aotearoa this year. His work though borrows from colourful queer pride symbols, where the jewel-like colours and camp elements instead ‘bend toward making positive space for healing and community building’.

Camp and queer art practices can, and need to, create works to ‘laugh rather than argue,’ and can celebrate pride and identity through visual spectacle. Art here is a celebration of the necessary healing possibilities of creation, in light, playfulness and pleasure.

Brittany Walker Smith works in sculpture and installation. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts with First Class Honours (Elam) and is currently studying her Masters of Fine Arts (Elam).

Caitlin Devoy works in sculpture. She has a Bachelor in Art History and Anthropology (Victoria), a Postgraduate Diploma of Design (Whanganui School of Design), a Postgraduate Diploma of Fine Arts (Massey) and a Master of Fine Arts with First Class Honours (Massey).

Shannon Novak’s works across multiple different art media including sculpture, installation, and painting. He has a Bachelor of Applied Information Systems (WITT), a Masters of Education (Massey), and a Master of Fine Arts (Elam).

Ellie Lee-Duncan is an artist, writer, and curator. They have a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Art History and English Literature (Victoria) and a Masters in Art History, with First Class Honours (Auckland). They are currently on a break from their PhD (Auckland).